“Digging Deep, Crossing Far” – Interview with Julia Tieke

Julia, first of all congratulations to an amazing exhibition. When did you first come across this phenomenon of POW camps for ‘colonial soldiers’? It is obviously not a very well-known part of German history.

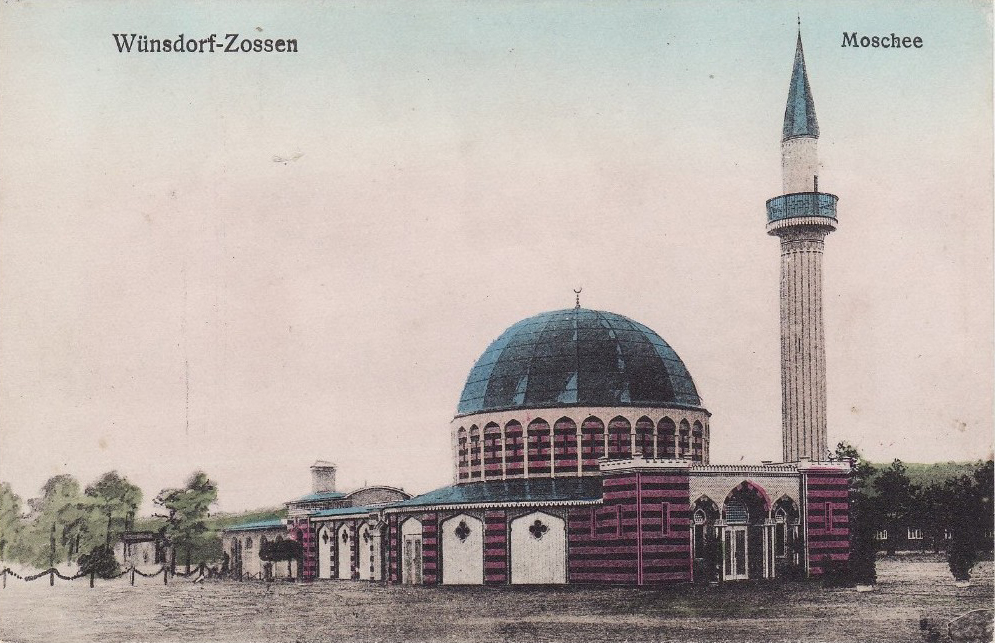

I came across it roughly two years ago when I read a short article in the weekly paper „der Freitag“ about the first German mosque which was built inside the „Halfmoon Camp“ for „colonial soldiers“ south of Berlin in 1915. I connected immediately to the site because a Syrian friend of mine lives there nowadays and so I started a research and interviews for a radio program about the camps.

What was the inspiration for the title: “digging deep, crossing far”?

It was a spontaneous working title at first and then we decided to keep it because it has two movements – horizontal and vertical –, that on the one hand describe our curatorial approach and that of the artists – digging deep into local histories of the First World War, and on the other hand the movement of “colonial soldiers” back then – crossing far. For the first time, a large number of soldiers from outside Europe were recruited to fight at the “Western front”. They crossed oceans and continents.

You point out that it should be seen as an early sign of globalization, as a total war. But until 2014/15, nobody really looked at this global dimension of it. Why?

There have been a few academic pioneers who worked on those questions before the centenary of WWI, but yes, the global dimension has been largely neglected. I guess it is connected to a general eurocentrism and a focus on the big battles sites which were in Europe mainly. Also, the Second World War has overshadowed the First, both in personal memories and family stories, as well as in history lessons or the academic world. In countries like India or Pakistan, other historical events were more important than the involvement of soldiers in WWI, namely Independence and Partition. With a cultural turn and after postcolonial debates, scholars have started to focus more on presumably side histories of WWI.

The main idea of your project was to combine scientific research with works of art: truth with beauty, if you like. What do you think is the major difference between the scientific and the artistic approach? Do you also consider this to be a part of ‘crossing far’?

It’s an interesting thought to consider this to be a part of “crossing far” – and indeed, Elke and I come from a background where interdisciplinary work is the norm, not the exception, so we tend to cross topics, formats, ideas. I wouldn’t connect scientific research to truth and art to beauty though. Of course, where a scholar will need to argue consistently, an artist is free in his approach and can be very random. Quite some scientific research has been done by now on global dimensions of the First World War, and thus we emphasize the artistic approaches in our project. The artworks develop from a discussion around the propaganda camps for “colonial soldiers” and from there around involvements of the soldiers’ countries of origin in the war. Art can ideally raise questions, radically comment on a topic and dig out forgotten stories.

Adorno coined this famous phrase, that after Auschwitz, poems – art – is no longer possible. How do you relate to this question? Isn’t a work of art about the horrors of war turning this horror per definition into something beautiful?

There wouldn’t be any art whatsoever anymore if we take this phrase literally and apply it to any “horror” in this world. Is a painting of a battle like Picasso’s “Guernica” making violence more aesthetic? I don’t think so. With the Islamic State, we have an example of a terrorist organization which should also be studied by its aesthetics, by the way. Their recruitment videos are often very professional and the images they use follow aesthetic criteria. The relationship between the horrors of war and aesthetics are pretty complex. With our project, we don’t aim at representing the First World War through art, but we invite the artists to concentrate on specific aspects and to work on them, and thereby shed lights on the history of science, for example if you look at how “colonial soldiers” were used as objects by scientists. This, for example, is less about the horror of the frontline, but the more hidden horror of power relationships within the war and science. On the other hand, we plan to show propaganda photographs from the time of WWI that show how certain images were used to convey political ideas (i.e. the superiority of the Germans). War is not only about bloody horrors, but also about image politics.

Speaking of artists, you picked Ayisha Abraham, Gilles Aubry, Surekha, Sarnath Banerjee, all representing different media. Tell us a little bit about your choice. Why those four? And if possible about the solutions these artists created by dealing with the material.

The Goethe-Institut Bangalore had invited us and was specifically interested in the local history regarding World War I. We therefore invited two artists who are based in Bangalore, Ayisha Abraham and Surekha, and whose works supplement each other very well, as Ayisha Abraham presents an individual story of her grandfather’s involvement in WWI whereas Surekha has deeply dug into the local military archive and presents a whole range of archival material. With Sarnath Banerjee, we wanted to introduce drawing as another medium besides documentary material, and he also provides the visitors with a broad view on the involvement of South Asia into WWI. The sound archives of the recordings in POW camps, are a well preserved and very interesting source, and we wanted a work on those recordings. As Gilles Aubry has intensively worked on colonial recording, epistemologies and listening situations, he was the ideal artist to work on that part of history.

Your starting point are the so-called “Halbmondlager”, the Halfmoon Camps. Sounds romantic.

The Halfmoon Camp was a POW camp and as such a rough site which also saw many POWs die. Nevertheless, it may partly have been a romantic idea if you take longing as part of romanticism. Max von Oppenheim convinced the German Kaiser to fund his “jihad program” of which the camp and its mosque were part, and some of the orientalists who worked in the foreign office seemed to have had less political aims, but actually quite romantic ideas about the friendship between Islam and Germany.

You sat on a panel with German author Steffen Kopetzky in Bangalore, who has been publishing this epic novel on World War I recently, “Risk”. Would you go as far as Steffen to say: The jihad is a German invention?

No. And actually, did he really say that? Historically, there had been a discussion about whether it was a German invention, but the concept of jihad is older than World War I, of course, and jihad is first of all a personal inner struggle, not a “holy war”. For sure, WWI Germany is an interesting example of how a state tried to make political use of a religious concept – and, by the way, mostly failed to incite Muslims which proves the popular assumption wrong that you can somehow press a button on a Muslim and he will “go to jihad”.

It is somewhat ironic, but it seems the German state was more tolerant towards Islam than nowadays. If you think about the closure of prayer rooms in German universities that happened recently …

Well, it was a clear strategic move and a double sided coin: the Germans back then opposed harshly to any non-European (who they called barbarians) to fight on European (“civilised”) ground, but as their enemies did so, the Germans then propagated they treat those foreign soldiers better than the French or British did. The German Reich clearly had middle- and longterm political goals, namely to establish good economic and cultural relationships with the Middle East for example, where they lacked colonies but had great economic interests. Still, the fact that the first mosque ever in Germany had been built by the state in a POW camp is a part of German history which I never cease to tell people as it is hardly known whilst it should be.

You show that the camps were opened up for research – so science came in because they were a failure?

The jihad program was rather expensive and not very successful, so the camp was more and more opened for science.

You have been listening to some of those recordings that were made back then, when ethnologists and linguists took over. Can you describe us your experience?

100 year old recordings that are well preserved are rather rare, and due to the linguist Wilhelm Doegen’s aim to record as many different languages and dialects as he could, the Berlin Lautarchiv holds a fascinating collection of songs, prayers, tales and personal narrations. The fact as such that we are able to listen to them today and also know the speakers’ names and place of origin through the files, is fascinating. Some sound very fresh, sometimes you can hear a laughter, one Moroccan miscounts in a row of numbers – these more personal moments are specifically touching, apart from the few personal stories we know of where soldiers recount their experience of the war.

You focused on the search for traces in Bangalore – and collected some remarkable facts. For instance that the term postcolonialism is justified, as Bangalore is still an important armaments production site. Have you been there?

You mean the armaments production site? No, we haven’t, and I am not sure if we actually could. We did visit a brand new military site though, a memorial site for fallen Indian soldiers. The remarkable thing was that on the stones they left a lot of free space for future casualties. It could simply be regarded as a pragmatic move, but it’s also creepy to see the history of future wars in the making.

What is it with the “Bangalore Torpedo”? We never heard of it before…

We hadn’t either until Surekha presented the Torpedo within her work. It’s a weapon that was first used in WWI and is still being produced and used today. It is a path-clearing device, e.g. barbed wire obstacles. It clears a 3 to 4 meter wide path, allowing to move forward. For the Berlin show of „digging deep, crossing far“, Surekha is expanding her work on the Torpedo in particular.

Julia, thank you for the interview – and good luck with your next projects.

Interview: Arqam Khan & Markus Heidingsfelder

Published with permission from the Lautarchiv at the Humboldt University, Berlin. For further enquiries, please contact the archive: www.lautarchiv.hu-berlin.de, lautarchiv@hu-berlin.de