“Dear Mr. Heidingsfelder” – “Dear Mr. Alpermann”: A Correspondence on the SCMP Op-Ed

Dear Mr. Heidingsfelder,

With great interest, I read your commentary in the South China Morning Post. Even though I am not one of those who are singing from the same song-sheet that claims Confucius Institutes promote espionage or otherwise endanger our freedom of science, some of the statements in your article made me very uneasy. Unfortunately, you use exactly the same argumentation patterns that are propagated by the official side in China: Whataboutisms in the direction of Afghanistan and Corona. I would expect a media scientist to critically reflect on these and recognize them for what they are, namely diversionary tactics.

Also, on the situation in Xinjiang, you simply repeat the PRC government’s “terror narrative” instead of asking why such fierce resistance is erupting after decades of PRC control over the region and supposed “development.” Even if Uyghur terrorists have partly taken a cue from Islamist groups abroad, the causes lie far deeper, are much more complex and, above all, are homemade. And terrorism should not be used to legitimize any kind of human rights abuses. For more detailed information, I refer you to my book on the subject. You can find the link in my signature below. It is published Open Access — do try it out if you can download it from China.

With kind regards

Björn Alpermann

—

Dear Mr. Alpermann,

Thank you very much for your email. It is nice that it is still possible to deal with each other in a respectful tone – in these turbulent times it is unfortunately anything but understood, even among scientists.

First of all, let me reply that I was quite hesitant to take part in such a debate in the first place. What ultimately prompted me to do so was the hostility towards my colleagues – mainly German sinologists who have tried to critically engage with Western coverage of China. They are by no means people who keep quiet about their criticism of China, not propagandists. Baerbock hasn’t made their lives any easier. You are certainly aware that name-calling in connection with public hostility can cause existential crises. Several sinologists were defamed in the Springer press (one of them was even more or less called upon by the so-called “lateral thinkers”). One of my colleagues was shocked by this public defamation, which is why this person has withdrawn for the near future from the mass media discourse, writing: The topic ‘Corona and China’ in Germany runs more and more out of control. I have to take a step back to recover. So much for my motivation. I think it is absolutely necessary to write against the anti-China discourse. As this colleague correctly said, the difficulty of positioning for China researchers lies in the fact that one has to fend off attempts of censorship and manipulation by the Chinese government on the one hand, and China-bashing in mass media (and probably also by American influence) on the other hand, i.e. one is always busy on “two fronts”.

As for your expectations towards a media scientist – recognizing something for what it ‘is’ would presuppose an objective point of view, from which one can then see things as they are. That is the strange motto of DER SPIEGEL: “Sagen, was ist” (Saying what is). But facts don’t lie around in the world, they are called into existence. And especially in this context, it is not easy to obtain reliable information. As you have surely seen, there is more behind my ‘whataboutism’ than just an absurd “Germans also had concentration camps!” (Indeed, I’ve read that before.) My point is a very simple thought, please check if it makes sense: Whoever argues morally – i.e. like Annalena Baerbock, i.e. refers to self-evident values that should be taken into account – cannot remove herself from this argument. On the contrary, moral communication is characterized precisely by knowing how to fulfill these moral demands on others oneself. While ‘whataboutism’ cannot serve to justify crimes, it can point to the questionability of moral argumentation. So, rather than being a distraction, it is supposed to direct attention to the character of moral communication itself.

In my view, a ‘values-led’ foreign policy is not politics – a realistic look at this social domain teaches that the preference value is ‘power’, not: freedom, equality, etc. The USA have managed to garnish their foreign policy with these values. Baerbock now seems to want to follow suit. I agree, terrorism should not be used to legitimize any kind of human rights abuses. I’ll spare you the next ‘whatabout’ at this point. Let me again refer to the excellent text by Kerry Brown instead, for whom the West has long lost its moral stature – and the reason is its fight against terrorism. This West – the Guantanamo-waterboarding-Murat Kurnaz West – now denies China the legitimacy of its own war on terror. That’s not without irony, don’t you think? Even if one – as you seem to do – may not consider the concept of terror to be readily applicable here. Friedbert Pflüger has been addressing Annalena Baerbock three days after my text in a piece for Cicero, writing: It is permissible, often even necessary, to express one’s own convictions and to promote them. However, one must be warned against overzealousness in the feeling of moral superiority. Other, partly older civilisations or countries with orthodox religious convictions do not like to be patronised or lectured. A values-based foreign policy should uphold the achievements of European civilisation, but the West has no reason for boastful self-righteousness. The Inquisition, the extermination of the Indians, slavery, colonialism, the Holocaust, chemical bombs on Vietnam, Srebrenica or Abu Ghraib – all this was not long ago. What right have we, who ourselves took centuries to enshrine human rights in Europe, to demand that other cultures adhere to Westminster standards here and now?

Some may call this ‘Whataboutism’, too.

All of this certainly comes up short in such a heavily abbreviated opinion piece – d’accord. I was also aware of the danger of being appropriated here. Again, my motivation was the increasingly sharp attacks on my colleagues and friends – to be accused of propaganda, of being a paid stooge, I was only too happy to accept. I will certainly read your book. Especially your inclusion-exclusion text interests me very much. That the contexts are complex should be clear, but complexity can be reduced.

Should you be interested, here is the longer, updated version of my Op-Ed:

Realo Turned Fundi – The Baerbock Doctrine. An Op-Ed by Markus Heidingsfelder

I have responded to some of your comments in the PS.

Let me know if you can imagine to publish a conversation between us on mediastudies.asia and maybe even join a larger round table that deals with these questions.

Best regards

Yours Markus Heidingsfelder

—

Dear Mr. Heidingsfelder,

Thank you very much for your e-mail and for pointing out the somewhat more detailed version of your opinion piece. First of all: I am always up for dialogue — even contentious ones. So if you’d like to organize something along those lines for the aforementioned website, I’d be happy to participate.

I agree with your assessment that sinologists who are unfairly and sweepingly attacked for expressing an opinion different from the mainstream discourse should defend themselves. So for the last ASC (Arbeitskreis Sozialwissenschaftliche Chinaforschung) meeting last month, I organized a roundtable discussion with two of the most vocal critics of German China studies. In their article, Andreas Fulda and David Missal make sweeping attacks on all those who do not take a position against the PRC regime — but in what I see as a completely indefensible manner. I certainly do not adopt such attacks as my own; on the contrary, I take action against them myself.

But when someone simply reproduces the contents of the PR government’s white papers without showing even a shred of reflection and criticism of them, that needs to be criticized in my view. And not, as may quickly happen in German media, because that person, for instance, heads a Confucius Institute, but because it is a violation of the standards of scientific work (and of common sense) to take the positions of a party to a conflict unchecked at face value.

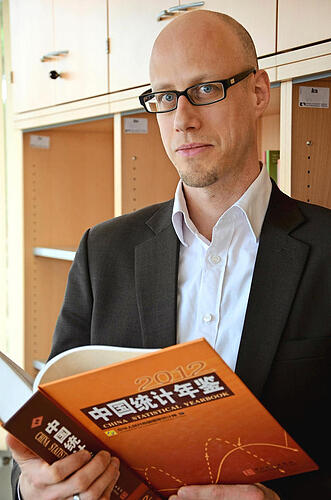

Björn Alpermann, Dr. phil., born 1972, Chair of Contemporary Chinese Studies at the University of Würburg, is currently leading the project “Social Worlds in China’s Cities” together with Prof. Dr. Elena Meyer-Clement – a subproject of the joint project “Worldmaking from a Global Perspective: A Dialogue with China”. From 2017 to 2018, he conducted the BMBF-funded research project “In the Face of a Gray Society: Social Institutions of Care for the Elderly in China.” From 2010 to 2016, he was coordinator of the BMBF-funded Competence Network “Governance in China” and head of the sub-project “Social Stratification and Political Culture in Contemporary Urban China”. At the same time, Björn Alpermann has been acting as spokesperson for the entire collaborative project since 1.10.2021. Selected books: China und die Uiguren, Würzburg: Würzburg University Press, 2021. Björn Alpermann, Birgit Herrmann, Eva Wieland (eds.), Aspekte des sozialen Wandels in China: Familie, Bildung, Arbeit, Identität, Wiesbaden: Springer 2018. Yu Keping 俞可平, Thomas Heberer, Björn Alpermann (eds.), 中共治理与适应: 比较的视野 Governance and Adaptability of the Chinese Communist Party–a Comparative Perspective, Beijing: Central Compilation & Translation Press, 2015.

I could not read Wolfgang Kubin’s article because it is behind a paywall. But what I was able to glean is that he understands censorship in China as part of everyday life there, even in academia, so one should not be particularly upset about it. Well, one can look at it that way: I would also not expect to be able to research and teach as freely at a Chinese university as I do in Germany. I would describe this expectation as rather naïve. Another question, however, is how far we want to let China restrict our freedom of research in Germany. There I see a need for action (but not in the way Fulda/Missal postulate). These debates, whether or how China research has to reorganize itself, are currently being conducted in an engaged manner. My impression is that those whose first socialization in China took place during the Cultural Revolution tend to have a very different view of current trends under Xi Jinping than younger scholars of China.

I am happy to attach my text on inclusion/exclusion. However, it is only a brief introduction to the thematic issue I edited. I would be happy if we could exchange ideas about this as well. Similarly, I find your work on the societal impact of coronavirus interesting. You are right that there are many parallels here. Your assessment that there is no legal requirement to vaccinate in China is correct from a formal legal point of view. However, it leaves out the fact that the local level (neighborhood committees) does build political pressure to vaccinate. China is a ‘mobilization regime’, and not a constitutional state.

But now again more fundamentally to your article:

1) Of course, you need a hook for such an article, and Ms. Baerbock as foreign minister has special responsibility for German China policy. Nevertheless, I think that this focus on her person is misguided, because it seems to me to hide more than to explain. I don’t want to ignore her personal mistakes in the election campaign, which you name (the full truth is that she – as a woman – was really exposed to unspeakable attacks ad personam). But the crucial point, in my view, is that both the FDP and the CDU had very similar demands and pitches in their election programs (with different weightings). If you focus on Baerbock and the Greens, you fail to recognize that the reorientation of China policy is currently being demanded and pursued by many political actors. It also ignores the fact that this is being negotiated not only in Germany, but also at the European level. The wording on the German-Chinese relationship that the three parties ultimately included in their coalition agreement is exactly the same as the one that has been used analogously by the EU since 2020 (“partner, competitor, systemic rival”). Interestingly, the dividing line in the discussion on this issue within the new coalition is between the SPD on the one hand — which wants to continue Merkel’s course of ‘mealy-mouthed behavior’ — and the two smaller partners on the other. So the SPD is far from having a “values-based foreign policy”. That’s why I find your references to the attitudes of former SPD ministers Struck and Steinmeier out of place. You can criticize them, but that says nothing about a “values-based foreign policy.”

2) I would like to clear up one misunderstanding: It is true that the FDP and the Greens do indeed use the term “values-based” in foreign policy. But there is no contradiction to the official Chinese position — in the sense that the former “moralized” while China argued realistically. On the contrary, the PRC side is at least as moralizing and continues to emphasize values in international relations. The difference is rather that Western critics of China emphasize individual liberties and universal human rights (perhaps too singularly — that could be debated), whereas China prioritizes states’ rights and the values of state sovereignty, territorial integrity, and non-interference in internal affairs. In addition, there are human rights, but they are defined and interpreted in very particular ways (collective rights before individual rights, substantive rights before civil liberties, etc.). When one reads statements from government sources on Chinese foreign policy, they are dripping with lofty values (“community of common destiny” discourse), so that the one-sided accusation that Western critics of China are “moralizing” must really stick in one’s throat. Again, one should not take this at face value. China, too, knows very well how to dress up its interest-driven foreign policy in soothing terms in order to distract from the core of its power politics.

3) What are the options? You proclaim: “Anyone who stands in front of the microphones and announces a dialogue is not holding one. Only two can play this game. And anyone who announces that she will be tough is maneuvering herself into a highly problematic position that makes what characterizes politics impossible – flexibility.” True, but it completely overlooks the fact that China’s government has made it unmistakably and repeatedly clear that a) there can be no dialogue for it on Xinjiang, Hong Kong, and similar cases because they alone take care of China’s “internal affairs”, and b) China is currently pursuing a hardline policy in these disputes that robs itself of any flexibility. The “mistake” of preventing dialogue instead of promoting it is committed at least as much in Beijing as in Berlin or Brussels.

With best regards

Björn Alpermann

—

Dear Mr. Alpermann,

Now that’s what I call a differentiated critique! I wish we had exchanged views earlier. The good thing about my SCMP ‘snapshot’ is that we are now in a conversation, and have moved from the opinion level to the factual level. For that alone it was worth it.

I readily admit that you know much more about the political details – for instance what the three parties included in their coalition agreement, or what ‘China slogan’ the EU agreed on last year. Sure – with a partner you talk, but to a competitor and ‘systemic’ rival you are tough. Seen in this light, Baerbock is merely spelling out what was previously agreed upon. But that does not make things any better. And of course it makes a difference whether politicians agree on a strategy – or whether the new German Foreign Minister, shortly after taking office, announces the execution of this strategy in front of the world’s microphones.

Before I respond to your points – and I very much appreciate that you took so much time for your e-mail – I would like to clarify once again what I was primarily concerned with in this opinion piece: to point out the double standard that is brought to bear in Baerbock’s statement. As my colleague Hans-Georg Moeller nicely put it, “dialogue and toughness” basically means permanent moral instruction from above on the part of those who know better. But with what justification? And if toughness, shouldn’t it above all be applied to an ally that is guilty of permanent violations of international legal norms that are unparalleled in recent history?

As far as Europe’s handling of refugees is concerned, we are confronted with a lot of ‘values-based’ talk – and a lot of tough action. Which is why author Christian Y. Schmidt demands: “The dying at the European external borders must finally stop. The news blackout must be lifted. Human rights in Europe – now!” I experienced this hardship first hand when a Pakistani family, friends of mine, Christians, was prevented from entering Germany for flimsy reasons and by means of high bureaucratic hurdles – they would not even allow them visiting their relatives. The Consul General at the time admitted to me that the unofficial instruction was: ‘Don’t let anyone in.’

And as far as ‘systemic rivalry’ is concerned, on a communicative level it does allow – excuse me, but the religious metaphor fits: to mantra-like (‘gebetsmühlenartig’) point out the shortcomings of the rival’s ‘system.’ In an interview for this website, sinologist Karl-Heinz Pohl has nicely summed up the central difference between the Western and the Chinese media reporting:

Of course, Chinese media are controlled by the government. They probably have a certain leeway, though, too. But although Western media are not controlled directly by the government, they are led by the prevalent political ‘Zeitgeist’. Regarding China this means, for example, to view China only from the perspective of her people lacking basic rights – not focusing, instead, on issues such as poverty alleviation, increase of a middle-class, and others.

To your reflections on the freedom of research: Within a theoretical framework, criticism is possible in China. Of course, no direct criticism of the government, that is well understood. My main task at UIC is to prepare students to study abroad, and without the ability of critical thinking, they will fail. Of course, art and science – just like all other social areas or systems – must be ‘free’, in the sense of ‘autonomous’. Anything else could well be called corruption. Just think of the “China Initiative” of the US Department of Justice that I mention in my post. It’s quite interesting how the Department of Justice justifies it: by pointing at possible “threats to academic freedom and open discourse from influence efforts on campus”. George Orwell would have loved it: Restriction is freedom.

But just as little should morality be a part of research – that is, a discrimination of persons and actions based on certain values. Instead, it is a matter of looking at the mechanisms of these judgments, the communication of disrespect, condemning a person as a whole. This may be easier for me than for other colleagues, because, so to speak, nothing social is alien to systems theory – it looks at everything with the same, cold eye, and asks: How does it work? Criticism thus rather in the sense of Kant. One can find fault with that, and a fault it is, it does not make any suggestions for improvement of society. One could say that this is exactly what characterizes the autonomy of science, but that is an open debate. Many of my American friends see it differently, they are disputatious democrats, even in their texts. They say: You make it too easy for yourself – and your non-normativity is itself highly normative. In my view, however, democracy is merely one form of government among others.

Formal-legal, compulsory vaccination: Of course, you are right – again, these are things that are legitimate in an opinion text in my opinion. There is pointedness here. I wanted to throw a stone in the water, so to speak. It made waves, that was the whole point. But ‘mobilization state’ I like very much! I didn’t know the term. What I perceive here, what already interests and fascinates me as a communication theorist, are the many campaigns. Most recently, the one that directly affects my journalism courses, which promotes the new guidelines for the entertainment sector.

To 1): I agree that the focus on Baerbock’s person is somewhat misguided. Her name primarily serves the purpose of assuming a kind of ‘social authorship’ for the complexity of political events. But tell that to the mass media please! No TV station wants to confront viewers with nameless analyses, information is always related to persons here, individual actors are constantly presented as agents, sorted out, singularized – politicians like Baerbock, or organizations like the Greens. Explaining that would have really overwhelmed this little piece.

To 2): One could accuse you of ‘whataboutism’ here (“the PRC side is at least as moralizing”)! Just kidding. It may well be that “statements from government sources on Chinese foreign policy … are dripping with lofty values (‘community of common destiny’ discourse)” – but I was concerned with Baerbock’s statement. A closer look at politics shows that it cannot do without hypocrisy – nowhere. Again, this is the cold view of systems theory: politics is not about values (human rights, the environment etc.), but about power. That doesn’t stop it from representing them. Which then prove useful to the parties in their election campaign. So that people can vote with a clear conscience: ‘I vote for those who protect the climate and propagate human rights!’ But of course you are basically right: when looking at the power practices of the U.S., we should not just be reproducing the discourse of China, but take a closer look at their systematic interplay. Marius Meinhof’s term for this is “dual power structure”. And this is precisely why scientific, sociological reflection and conceptualization is especially urgent today. As mentioned earlier, my Op-Ed does not claim scientific status – about which the category already informs.

To 3): Well, I think the options for us scientists are clear – to observe these things as accurately as possible. An important part of this accuracy is never losing sight of our own perspective, as difficult as it may be at times.

Best regards

Yours Markus Heidingsfelder

—

Dear Mr. Heidingsfelder,

I am also pleased about our exchange. I don’t want to go into all the points in detail now. Perhaps only this much: double standards can also be found on both sides. And the new government (at least the Green Party) has already taken it upon itself to make European policy more honest, especially with regard to the issue of refugees. Whether they will succeed depends, as you rightly point out, less on morality than on questions of power. But the ambition is at least now there where it was lacking before.

Indeed, about the German/European immigration policy one can really often only wonder and get angry, as you also describe. I felt the same way, for example, when in the summer of 2020 the German media got terribly upset with the Trump administration for trying to close the borders to international students. At the same time, I had to witness how numerous international freshmen we had admitted for the winter semester 2020/21 were not granted visas for Germany in their home countries – with exactly the same arguments as in the USA under Trump. But hardly anyone here was interested in that (I tried to get the media on it – in vain).

As far as the systems-theoretical glasses are concerned, you are certainly right: they tempt one to retreat to a purely analytical position. I rather stick with theories of reflexive modernization and would hope, analogously to Ulrich Beck, that in principle also a turning point is conceivable, at which a society that thinks about itself can also take measures to change the system. I would even say that if this does not succeed, for example, in the matter of climate protection, then that would be fatal.

On your question about urbanization processes: I am currently leading a collaborative project on “Worldmaking from a Global Perspective: A Dialogue with China” and within it the sub-project “Social Worlds: China’s Cities as Sites of World Generation”. Among other things, we are trying to get to the bottom of the questions you raised. However, our work is greatly hampered by the fact that there is practically no field research access.

With best regards

Björn Alpermann

—

Dear Mr. Alpermann,

I am just reading in your excellent, amazingly detailed Xinjiang book. I agree with you that we cannot do without a comprehensive historical contextualization. Due to its richness of detail, I’ll have to save a close reading for the vacations.

Because of our correspondence, I have changed my text again, and I also point to your work on Xinjiang. The problem remains: to get reliable facts. I’ll leave it at that now. The main thing was to take a stand against the anti-Chinese discourse in the German media, which is now being publicly supported by Baerbock.

But I couldn’t help smiling when reading today’s commentary in DER SPIEGEL: “Is the values-based foreign policy over before it’s begun?” Even if I might then smile with ‘the wrong people’. Poland’s Foreign Minister unfortunately strikes quite similar tones as I do, only that instead of ‘reality’, he speaks of an ‘ongoing practice’ that Baerbock needs to face up to. Of course DER SPIEGEL demands value-based action here. Luhmann’s idea was: this high morality of the mass media is a compensative for their sensationalism, their preference for conflicts. Either way, thanks to you, I was already aware of the threefold motto mentioned there.

Please find attached an article by Sebastian Conrad for the FAZ that looks at contemporary Western discourse on China from a historical perspective. Funnily enough, Karl-Heinz Pohl had a little earlier also used the expression “Yellow Peril 2.0” to characterize a lecture by his colleague Sebastian Heilmann. The thesis that the image of China rather says something about us and our political preferences than about China is also what his contribution boils down to, something he had already pointed out a little earlier. In systems theoretical terms: Every observation points back at the observer.

Best regards

Yours Markus Heidingsfelder

—

Dear Mr. Heidingsfelder,

Thank you very much for your effort: yes, I already know the Conrad article. He is one of my collaborators in the Worldmaking project. Nice that you got the XJ book. I’m still reading excitedly in the minima sinica edition you sent: Thanks for this, too!

You are right, the issue of information gathering is central to a case like Xinjiang. That is why I engage in extensive source criticism in the relevant part of the book. What you report about the lack of access of your Chinese friend, I have also heard from a German journalist friend.

Regarding your suggestion to publish our exchange: I can’t quite imagine what form that would take yet. But if you would make a suggestion on this, I am certainly open for it.

Best regards

Björn Alpermann