Every good garden needs fertilising: Scientific cooperation with China must not slacken despite all the problems – By Nadine Godehardt and Björn Alpermann

Seldom have German-Chinese relations in their 50-year history been as difficult as they are today. Although the People’s Republic of China remains Germany’s most important trading partner in 2021, the positions of the two sides on geopolitical issues could hardly be further apart.

The opposing assessment of the Russian war of aggression on Ukraine, China’s alternative development path and the increasing distancing from Western liberal ideas of constitutional democracy are just a few prominent examples. China’s path impressively underlines that modernisation does not have to go hand in hand with Westernisation. Closely related to this is the feeling of alienation that is spreading in Germany and Europe towards China. The fact that China’s economic rise is not matched by any political rapprochement to “our” (liberal-democratic) way represents for many of those who for decades believed in the slogan “change through rapprochement” probably the greatest disappointment. The Federal Government already emphasised in its coalition agreement that German policy would shape “relations with China in the dimensions of partnership, competition and system rivalry”. The exact understanding of system rivalry is still undefined. Each department is called upon to contribute to a “comprehensive China strategy in Germany within the framework of the joint EU-China policy”. This also applies in a central way to cooperation with China, which has often been harshly criticised in recent months by politics and popular science. The accusation is that German science, instead of making the People’s Republic more open and democratic, has placed itself in dependencies, from which it must now be rescued as quickly as possible. It has put its values on the line – partly naively, partly blinded by a desire for recognition or guided by financial motives, it has contributed more to building up a technological rival than to promote its own scientific progress. It fits with this that the Federal Minister of Research, Stark-Watzinger, calls on German universities to “generally [withdraw] everywhere where we would help China gain an advantage in system competition”.

A crucial point is forgotten here. For German-Chinese academic relations in particular, the difference and competition between the political systems has always been present. However, the way in which this has been changed over the decades is not only due to the changes in Chinese science under Xi Jinping. It also has to do with the fact that the liberal Western world order is no longer what it used to be.

The structures of this order, its institutions, organisations and norms, still exist, but they can no longer provide sufficient stability and security. The many interlocking crises – financial crisis, refugee crisis, Covid 19 pandemic, Ukraine and Taiwan, but also the rise of populist forces in Europe and the USA, as well as the trend of “de-democratisation of democracy” – are exposing the cracks in the liberal order. The insecurity thus created is projected outwards onto the authoritarian “other”. These developments also have an impact on science and research. They enable Chinese actors to actively shape the scientific landscape, its norms and scientific cooperation in their own interests. At the same time, this situation unsettles politics and research, even though German-Chinese exchange in science has become increasingly close over the last three decades. The Chinese, for example, account for the largest number of international students at German universities, and Chinese academics are increasingly more and more frequently visiting Germany. Under the auspices of a relationship with China that is perceived more as a systemic competition these research connections are now being viewed more critically and in some cases scandalised. This is shown by the reporting on the China Science Investigation by an international research collective. The investigation reveals direct collaboration between European university staff and co-authors working for the Chinese military in around 3,000 cases. These are less than one percent of the 350,000 articles investigated. In the course of these revelations, however, only absolute numbers are mentioned, not ratios. The result is the impression that all scientific collaborations with China are suspect.

Science is certainly be called upon to take a closer look at whom it cooperates with in future. In addition to the proposals of the German Rectors’ Conference, it would make sense to take further steps to advise researchers through offices in universities and research institutes that are familiar with China. The fact that a corresponding call for proposals by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research from 2021 (Regio-China) has not been completed to date is not surprising in view of the recent funding difficulties of the ministry. Without additional funding, the increase in China competence mentioned in the coalition agreement will not be achieved. And China competence is the key to strengthening our science system against attempts at interference.

It is to be welcomed that the German government wants to rebalance its partnership with the People’s Republic of China half a century after the establishment of official relations. But a foreign and cultural policy guided by values still remains politics and thus “the art of the possible”: it is not a special request show. To those who hope to change China with lectures from the outside, one would like to tell with the famous German literature critic Marcel Reich-Ranicki: “You cannot fertilise a garden by farting through the fence.” Instead, we must look for ways to foster cooperation with difficult partners who do not share our values, in areas where they benefit all of us, first and foremost in climate protection, the most urgent task of our time, without relativising or even abandoning our values in other areas. Where the boundaries between these areas run and which instruments are to be used, will necessarily be controversial. This is how it should be in an open society.

In any case, we cannot preserve our (scientific) freedom by limiting it ourselves through prohibitions on cooperation and excessive constraints.

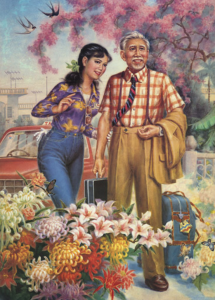

Translated from the German text by Tina Chen. Image selection: Bella & Katherine

Original text: Der Tagesspiegel, NR. 25 008 / 9. SEPTEMBER 2022, page 6.