Virtual Classroom Series: Interview with Georg Fahrion

Arthur: Guten Tag! I was wondering if growing up during the Cold War, before the Berlin Wall fell, had any impact on your career as a journalist?

I find this question quite interesting as it pertains to my perspective on the world. But even though you might think I’m older, I’m actually not that old! (laughs) I was born in 1981. My worldview wasn’t influenced so much by the Cold War, because I was too young. Depending on one’s point of view, it could be argued that the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 or the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 marked its end. I was eight or ten years old during those events, so they did not leave a profound impact on my consciousness, given my lack of political awareness at that time. Instead, I consider the decade that followed, the 1990s, to be of greater significance in shaping my worldview.

Back then, it appeared that the Americans had won, the Soviets were gone, and according to Fukuyama, this was the end of history, implying that liberal democracy and capitalism were the unavoidable fate of humanity. This notion informed my understanding of politics during my youth. It took me some time to understand that the culture and political system I grew up in were not the universal norm, but merely one of many possibilities. Learning to accept the existence of diverse systems and ways of life was a gradual process, but one that I eventually came to appreciate. As a young person, it is natural to gravitate towards the familiar and to embrace what has been one’s normative experience, particularly without broader exposure to the wider world. For me personally, the realization that there are diverse cultural and political systems was a protracted process.

I cannot pinpoint exactly when it began, but I believe such a process is a natural part of personal growth and maturation. My political consciousness has been shaped by the post-Cold War era, my own personal history, and a growing awareness that many alternative paths exist in the world.

Aurora: Could you share some tips on how to ask tough questions during an interview without causing the interviewee to abruptly end the interview? Have you ever been in a situation like this, and if so, how did you handle it?

Asking challenging questions can be difficult because nobody likes to be put on the spot. The approach you take really depends on the type of interview you’re conducting. For example, if you’re interviewing a small-town farmer and want to learn about their rural livelihood, you would likely take a different approach than if you’re interviewing a politician accused of bribery or a business leader.

The setting of the interview is also important. If you’re conducting an interview in a live situation, such as a TV studio or during a press conference, your interviewee cannot just walk away. Asking challenging questions in such situations has a bigger chance of success. In my experience, it’s important to be respectful but persistent when asking challenging questions. Try to understand the person’s perspective. It still might happen that you don‘t get anywhere, but that’s okay. You can always follow up at a later time.

To get an answer to a challenging question, preparation is key. It’s not very promising to simply ask someone directly if they made a mistake if you don’t have any background information. Instead, it’s important to have documented evidence and to be knowledgeable about the situation. If you want to get anywhere, you must do your research. For example, you might say, “You have been accused of bribery. Can you comment on the bank statement that shows money being transferred from a government account to your private account?” If you are well-prepared and persistent, you stand a chance to get to the truth of the matter. Politicians, in particular, are accustomed to avoiding difficult questions and changing the subject, so it’s important to press them and not let them hide behind hollow phrases. Again, if you didn‘t do your research, your chances are slim.

In a different situation, such as interviewing a rural farmer about their life, it’s important to approach the conversation with gratitude and respect. This is probably not a scenario where you’d ask hard questions. As a journalist, I have found that being well-prepared and respectful can help to facilitate productive conversations.

In Germany, journalism is about addressing problems and criticizing the government when necessary. The concept of journalism in China is quite different. Journalism should contribute to and support the government’s stance by promoting their voice. Instead of criticizing the government’s actions, journalists should work alongside them. These are two very different ideas of what a journalist should do.

Yawen: Have you ever been in a situation where someone walked out on you after you asked tough questions?

Yeah, definitely. Just two weeks ago, I was in Qingtian in Zhejiang province and I wanted to talk to the administration about an initiative where the police had set up service centers abroad. I uncovered something they didn’t want to discuss and pressed for more information. They basically said they didn’t have the authority to speak about it, and promised they’d set up an interview for me with their superiors, but that never happened. And that was the end of our meeting. It happens all the time, but what can you do?

Yan Han: What’s your take on the prevalence of surveillance cameras in China?

Well, some of the questions I’ve been asked require a nuanced response, and yours is no exception. First off, I must say that China is remarkably safe compared to many other places I’ve been to. Street crime is low, lower than in my home country of Germany, thanks in part to the extensive surveillance infrastructure.

However, this also means that people’s movements are constantly being tracked, including mine as a journalist. From a personal perspective, having grown up in a liberal society, I find the idea of being constantly monitored and tracked disconcerting. Facial recognition technology can instantly reveal my location to any authority. And not just my movements, but also the people I meet can be monitored by the authorities. Personally, I find this unpleasant, and it makes the job of journalists in China more challenging.

Serena: Do you prefer working in Germany or abroad? And what are the differences between the two working environments?

Born in 1981, Georg Fahrion initially pursued political science with a focus on international relations at FU Berlin. He specialized in the Middle East and spent two semesters in Tel Aviv. After completing his studies, he attended the Henri-Nannen-Schule in Hamburg in 2009/10. One of the mandatory internships he completed was at Financial Times Deutschland (FTD), which offered him a one-year position as a substitute Asia editor in the foreign department after he completed his journalistic training. At the end of 2012, FTD ceased publication and Fahrion transitioned to the Gruner+Jahr family’s business magazine “Capital” in Berlin. There, he continued to write about Asian topics and increasingly focused on China. At the end of September 2019, Fahrion began his position as China correspondent for Der Spiegel in Beijing. Immediately thereafter, the unrest in Hong Kong peaked, followed by the presidential election in Taiwan, and then came the coronavirus pandemic. “I’ve only known China in a state of exception so far,” Fahrion says. “It’s all the more beautiful that this time is now over.” Photo: private. Thanks to ChinaHirn for providing detailed biographical information on our interviewee – whoever is interested, here is the long version of his career (although in German).

That’s a great question, but it’s also a complicated one. I’ve worked in Germany, China, Myanmar, and a few other countries. When I’m on assignment in a country other than my country of residence, I usually stay for a week or two and then fly back home. So, I can only really compare Germany and China. They are very different indeed.

As a foreign correspondent in China, far away from headquarters, I don’t have a boss who checks when I arrive and leave the office or how I spend my work hours. Because of the time difference with Germany, I often work late to meet deadlines, but I also arrive at the office later than I would at headquarters. I believe I work more than the 40 hours per week stipulated by my work contract, but it’s up to me to decide when and where to work. It’s very liberating to have complete control over how I organize my work. If you work in headquarters, your time is structured by regular hours and meetings, which can be helpful for some people, but I personally prefer the freedom of working without supervision.

The work environment in Germany is very different from that in China because the definition of journalism is different. In Germany, journalism is about addressing problems and criticizing the government when necessary. My handler in the foreign ministry in Beijing has explained to me that the concept of journalism in China is quite different. According to their view, journalism should contribute to and support the government’s stance by promoting their voice. Instead of criticizing the government’s actions, journalists should work alongside them. The idea is to bring the public along rather than to showcase dissenting opinions. These are two very different ideas of what a journalist should do. My organization in Germany expects me to do a kind of journalism – and that happens to be my own idea of journalism, too – which often can be conflicting with what the Chinese government would like to see from me. As foreign journalists, we often cover topics that the government doesn’t like.

The Chinese government has an interest in having foreign journalists in China, because they want to be perceived as being open and as upholding the freedom of the press. Unlike our Chinese colleagues, we foreign correspondents do not fall under Chinese censorship, as we publish abroad. Hindrance to our work comes in different ways, such as that we don’t get access to sources or locations. Especially when we do research outside the big cities, we will often be followed, or we get physically blocked from places of interest. None of these things happen in Germany.

So, for me, it’s complex: Working as a correspondent gives me freedoms – regarding the organization of my work – which I wouldn’t have in Germany. At the same time, my work here in China is certainly more challenging and I’m facing more restrictions. That notwithstanding, I find it tremendously interesting and a great privilege to be here and learn. There may be days when I dislike the circumstances a bit, but for the most part, I really enjoy it. To sum it up, I think I prefer working in China than in Germany.

Iris: My question is about Hu Jintao being taken away from the scene at the 20th National Congress of the CPC. How do you view this situation? I know it’s a big topic in Western countries, so what are your thoughts on it?

You are right, it was definitely a big issue in the Western media. It’s all guesswork because we don’t really know what happened there. The official explanation is that Hu Jintao was unwell and had to rest and recover offstage. Everyone knows that Hu Jintao’s health isn’t great, given that he’s a 79-year-old man. But there’s another version that suggests there may have been some political significance to it. The official statement said that it was Hu Jintao’s own aides who took him offstage, but we know that one of the men who guided him away was in fact a subordinate to Ding Xuexiang, who was then Xi Jinping’s right-hand man.

Of course we don’t really know what’s going on behind the scenes. But if you watch video footage from the meeting, you can see that Mr. Hu didn’t want to leave. One of the aides had to lift him up from his seat. Hu Jintao tried to take his documents with him. Li Zhanshu, who was sitting to his side, pulled the documents away from him. Hu Jintao stood behind his chair for a while, debating and discussing. Eventually, he and the aides left, but it’s pretty clear that he didn’t want to.

No matter what the true reason really is, I think it’s a pretty powerful symbol. Whether there were political reasons behind it or simply Hu Jintao’s poor health – to me, the incident demonstrated not only how much Hu Jintao has aged, but also how strong Xi Jinping really is, because he had Hu Jintao removed from the stage irrespective of his will. So it’s very symbolic, indicating that the old networks don’t play as important a role anymore. Hu Jintao’s Communist Youth League faction, Jiang Zemin’s Shanghai Gang – they obviously have lost a fair bit of their influence. That, I think, is the significance of the incident.

Akira: I’m curious, how do you manage to get the answers you want during interviews, especially when the questions are tough and the interviewee may not be willing to answer? Any tips? Also, could you share some examples of times when your method worked or didn’t work?

As we discussed earlier, I believe it really depends on who you’re talking to. Every journalist has a unique work style that is influenced by their personality. In my case, I’m a tall man with a beard. It happens that people get intimidated by my physical presence, which can make it harder for me to get the answers I’m looking for. To overcome this, I usually invest 15 minutes to warm them up and make them feel comfortable around me. I start by talking about something light and non-controversial, and this helps them to feel like I’m approachable and open. I find that this helps to build trust, and they’re more willing to open up to me.

In my role, I’m not assigned to a specific beat, I don’t follow a particular political party or politicians. Which means, I usually work in an environment where people deal with media professionally as part of their daily routine. Instead, I travel and meet people from different walks of life and try to understand their world. I’ve found that by being kind, listening attentively, and showing a genuine interest in people, I’m able to get better interviews. As for specific examples, I can’t think of any off the top of my head, but I’ve definitely had times when my method worked and times when it didn’t. It really depends on the situation and the person you’re talking to.

SPIEGEL covers are decided at headquarters in Germany, our team in China wasn’t part of the process – when we woke up the next morning, the cover had already been printed. I personally am unhappy about that cover, which I have said on many other occasions. It wasn’t great for us, as it has not helped our work in China at all.

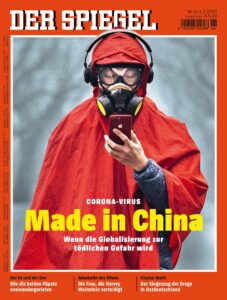

Cecilia: What is your opinion on the Western perspective towards China? Do you agree that it is overly critical? For example, there was a front cover headline in your magazine, “Made in China,” referring to the Covid virus. The Chinese Embassy in Germany expressed strong criticism of this cover. What is your take on that?

I know what you’re getting at. I was not pleased with that headline. That particular story examined the interconnectedness of the world. It was our first cover story on the pandemic, published on January 31st, 2020, one week after Wuhan was sealed off. Our medical correspondent, a German journalist who is a medical doctor by training, predicted at the time that the virus would be unstoppable. At that time, many people outside of China thought that the epidemic was a problem for Wuhan and Hubei, but they did not expect that it might affect their own lives. This story explored how this was a misconception, given the virus had already spread, there were cases in Bangkok and Seattle. It was an issue not only for China, but for the whole world, which is interconnected and globalized.

The headline was an attempt at a play on words. I believe the idea was to make a reference to globalized supply chains and globalization in general. SPIEGEL covers are decided at headquarters in Germany, our team in China wasn’t part of the process – when we woke up the next morning, the cover had already been printed. I personally am unhappy about that cover, which I have said on many other occasions. It wasn’t great for us, as it has not helped our work in China at all.

That being said, I don’t know if you had the opportunity to read the article, which we translated into both English and Chinese to help convince our critics. Among many other aspects, it speaks about Covid giving rise to anti-Asian racism in Germany and other parts of the world. The article was written at a time when there wasn’t yet much awareness of this issue. I don’t think the piece is hostile towards China. Unfortunately, the cover design was perceived as such.

Uki: What’s your take on China’s zero-Covid policy that was announced three years ago? Personally, I think it’s a bit of a dilemma. On one hand, there are people advocating for human rights, but on the other hand, there are still a lot of people getting infected with COVID-19.

As for the dilemma you mentioned, it is indeed a complex issue. Weighing freedoms against the protection of public health is a delicate balancing act, and different countries and societies have found different approaches during the pandemic.

I think that at the outset, China did an excellent job with the zero-covid policy. This holds true especially for the early days of the pandemic. It worked in terms of protecting lives. Now, with the new omicron variant, the policy doesn’t work as well. The government focused on lockdowns and testing rather than on vaccinating the elderly, and that’s going to be a problem going forward. The good news is that omicron is less pathogenic than the previous variants, therefore fewer infected people will die. However, if there are still high percentages of vulnerable groups, such as the elderly, who haven’t been vaccinated, that constitutes a problem.

Kris: If you were a new reporter and you wanted to write a feature article about a celebrity, but you couldn’t interview them in person, how would you go about finding other sources to include in your profile piece?

If you want to write a feature on a celebrity but can’t get an interview with them, there are other resources you can focus on. One approach is to talk to people around the star and see who is willing to speak with you. There is a legendary Esquire article from 1966 called “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold”, where the author follows Frank Sinatra for months, never gets an interview with him, but speaks to many people around him and in the end manages to write a profile that captures him very well. You may not have the luxury of choosing from among the thousands of people in your star’s orbit, but you can make the most of what you can get. A good starting point might be the star’s school, where former classmates and teachers may have valuable insights. You can also try to research the celebrity’s past interviews or public appearances to gain a deeper understanding of their personality and perspective.

I do think it’s important to present news and information in a way that’s engaging and doesn’t put our readers or viewers to sleep. That’s part of the service we provide as journalists. But if someone is sacrificing accuracy just to be flashy and sensational, that’s where I draw the line.

Daniel: When you are writing political journalism, which sources do you tend to get your news from?

When it comes to political journalism, my sources depend on the news environment. In China, we don’t have access to some of the sources we would normally use in places like Germany. It’s important to have a good understanding of the political landscape, which includes on-the-ground reporting and insights from academics and experts. While it’s rare to get interviews with active politicians in China, we sometimes have the opportunity to speak with diplomats who can offer second-hand insights. Social media is also crucial in China, and having colleagues who are knowledgeable about the different platforms and trends is extremely helpful. Personally, I’m fortunate to have a great Chinese colleague who has been working with us for over 13 years, and who is extremely knowledgeable.

Xin: I have a question about whether political journalism can be entertaining.

Certainly, I think the priority of political news is to inform rather than entertain. However, that doesn’t mean that political news has to be boring. One approach to making political news interesting is to focus on the people involved in politics – those who make decisions and those who are impacted by them. It can be interesting to look at who is making these policies and why, to provide context and relevance for readers. Rather than writing about politics in an abstract way, it can be more engaging to show how political decisions influence real life. For example, exploring the impact of policies on individuals and communities.

Yawen: I think, all journalism has some element of entertainment. But nowadays it seems like there’s more of a push towards excessive entertainment. Personally, I don’t necessarily agree with that view. I don’t think it applies to all forms of journalism because there are still plenty of outlets producing serious, excellent work. I’m not one of those people who thinks that everything is getting worse and worse.

Now, as for entertainment, I do think it’s important to present news and information in a way that’s engaging and doesn’t put our readers or viewers to sleep. That’s part of the service we provide as journalists. But if someone is sacrificing accuracy just to be flashy and sensational, that’s where I draw the line. However, I do believe that there’s still a lot of great journalism out there, you just have to know where to look.

Yawen: Into Der Spiegel, I guess?

(laughs) You said that!

Doris: You mentioned that the Chinese government welcomes foreign journalists to Beijing to show their openness to the world. I’m curious, how cautious do you have to be when reporting critically about the Chinese government? Have you ever experienced negative consequences from your reporting?

I do have freedom of the press in the sense that I can write and publish whatever I want, but that’s only because I get published abroad and not in China. I do not have the same freedom when it comes to conducting research. There have been instances where authorities have monitored our sources and prevented us from accessing certain places or even kicked us out of certain places.

As to my personal safety, I’ve been in a few unpleasant situations, but I haven’t been physically threatened. I still want to believe that the worst that can happen to me is to be kicked out of the country. My foreign passport provides a fair bit of protection. What worries me more is the safety of our Chinese colleagues and our sources. This is something that concerns me more than anything else.

Serena (in German): Lieber Herr Fahrion, vielen Dank für das Gespräch!*

* Dear Mr. Fahrion, thank you very much for the conversation! (The typical closing remark at the end of every Spiegel conversation.)

Transcript, remarks: Katherine, Molly, Bella. Captions: Serena. Proofread: Markus Heidingsfelder. Layout: Molly.